Bernstein, Sondheim and the initiation of a freshman

Mass and Company helped propel me into a life in musical theater

I had barely finished unpacking my boxes in Rodney C, my freshman dorm at the University of Delaware, when I saw a flyer taped to a bulletin board: a bus trip to the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., to see the premiere of Leonard Bernstein’s Mass. Like most young adults of my generation, I knew Bernstein as a telegenic conductor who appeared on the Zenith in the family room leading the NY Philharmonic. My knowledge of Bernstein’s work as a composer was limited—I had a high school friend with whom I’d shared an interest in contemporary classical composers, but our tastes were much more European and pretentious: Varese, Penderecki, that noisy lot. As for my religious background, it was Unitarian, not Catholic, so any knowledge I had of the ritual of the mass came from Latin class and James Joyce. So I can’t quite say what compelled me to buy a ticket. None of my friends were going—I had no friends at UD yet. I was sixteen, alone, and for reasons I still don’t fully understand, I boarded that bus on September 18, 1971.

What I encountered that night didn’t just expand my idea of what musical theater could be—it detonated it.

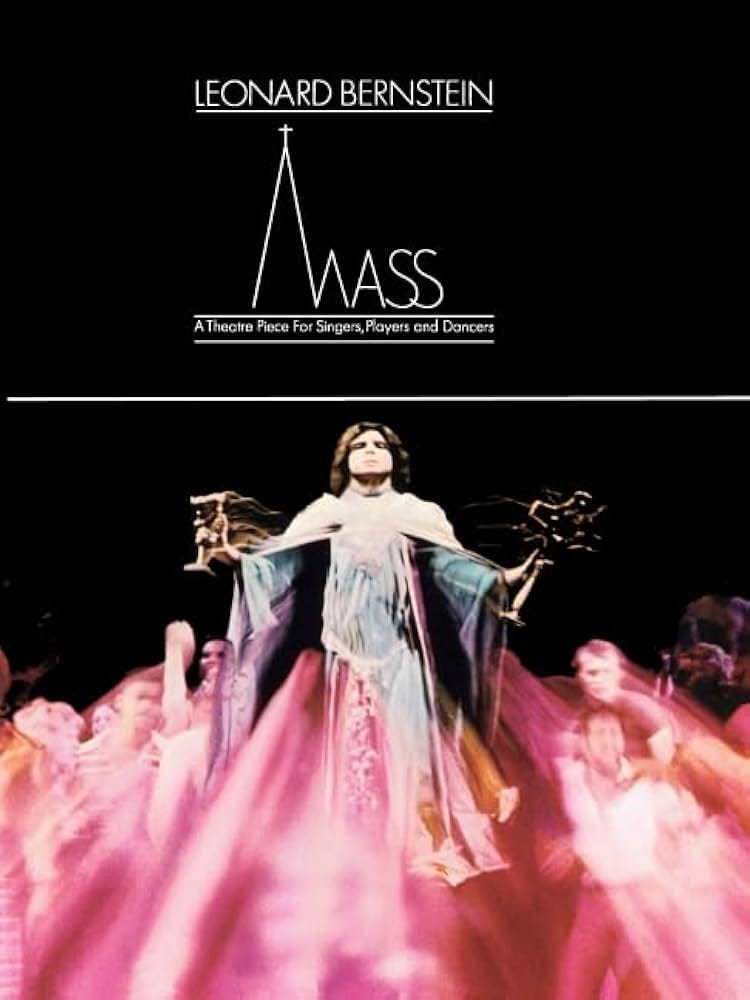

I hadn’t the least idea what to expect. Would it be a musical, like my high school’s production of Guys and Dolls? An orchestral concert? An opera? Some kind of religious ceremony? I had yet to see my first Broadway show, and my experience of “serious” music was mostly limited to record albums I’d borrowed from the music library at the local college. I had no frame of reference for what I was about to witness, no category in which to place it. The program said “theater piece for singers, players, and dancers,” which told me nothing. I sat in my seat, bewildered before it even began, trying to orient myself. What was this?

The lights dimmed, and before anything appeared on stage, sound began to surround me. A quadraphonic prelude played from speakers positioned in the four corners of the hall, voices and instruments swirling around the audience in a disorienting, immersive wash of sound. I had never experienced anything like it. Then came the marching band—brass blazing, drums pounding—processioning up the aisles from the back of the theater. The audience turned in their seats. The spectacle was already among us, not contained on a proscenium stage but invading our space, claiming the hall as a site of ritual.

What followed was two hours of organized chaos: a sprawling collision of liturgy and rock, classical orchestra and street theatre, solemnity and irreverence. Bernstein had assembled a cast of hundreds—singers, dancers, a boys’ choir, a marching band, a rock band, a full orchestra. The work lurched between musical idioms with reckless ambition: Gregorian chant gave way to jazz, then to atonal dissonance, then to gospel-inflected rock. It was overwhelming. I couldn’t tell if I was watching a religious ceremony, a protest, or a nervous breakdown set to music.

And then came the moment that seared itself into my memory. Alan Titus, playing the Celebrant—a priest-like figure who had led the congregation through the entire Mass—stood at the center of the stage during the Dona Nobis Pacem, the plea for peace. The music swelled into a driving rock beat, electric guitars and drums pounding with almost violent intensity. Titus, who had begun the evening in vestments and ceremonial calm, was now unraveling. The ritual was collapsing. And then, in a sudden, terrifying gesture, he shattered the chalice.

The music stopped.

The silence was absolute. For a moment, the entire theater seemed to hold its breath. The Celebrant stood among the shards, his faith—and perhaps the faith of the entire ritual—broken. It was shocking, visceral, and utterly theatrical. I had never seen a musical do this: stop time, shatter illusion, confront its audience with a moment of raw, unresolved crisis.

I left the Kennedy Center that night disoriented, exhilarated, and profoundly changed. I didn’t have the vocabulary then to articulate what I had witnessed, but I knew I had encountered something that redefined the boundaries of the form. Mass wasn’t entertainment. It wasn’t even just theater. It was a provocation, an argument, a spiritual and aesthetic reckoning that demanded something from its audience—attention, engagement, discomfort, thought.

The inability to categorize it was itself part of the revelation. Whatever it was, it refused to stay inside the boundaries I thought existed. It was a work that announced, through sheer audacity and scale, that the rules I thought governed musical theater—or any theatrical form—were negotiable, breakable, expandable.

For a sixteen-year-old who had grown up on high school productions of Once Upon A Mattress and My Fair Lady, this was a revelation: musical theater could be vast, unruly, dangerous. It could ask questions without answering them. It could challenge rather than comfort. And it could leave you shaken, unsure of what you’d just witnessed but certain that you’d witnessed something.

I’d come to UD enrolled as an English major, but during orientation week I attended a theater performance and immediately felt the energy and camaraderie of the drama kids. I knew I’d found my tribe. The experience of Mass, coming so soon after, reinforced my feeling that whatever I did in college, it had to involve theater and music. In September, I auditioned for the school’s production of The Glass Menagerie, and somehow, astonishingly, was cast—well, double-cast—in the role of Tom. And I learned this production was scheduled to tour to British universities and schools in January 1972. It all sounded very fancy and exciting to a precocious sixteen-year-old.

The Glass Menagerie wasn’t a musical, but it did have distinctive incidental music by Paul Bowles, and this was my first encounter with a straight play with bespoke music. I knew movies had musical scores, of course, but there was something about the music cues for that play that made an impression on me. The way music could underscore emotion, create atmosphere, mark transitions—it wasn’t foregrounded the way it was in a musical, but it was essential. It wasn’t too long (1980, actually) before I composed my own incidental cues for a production of The Glass Menagerie at the Delaware Theatre Company, a fledgling professional company in Wilmington.

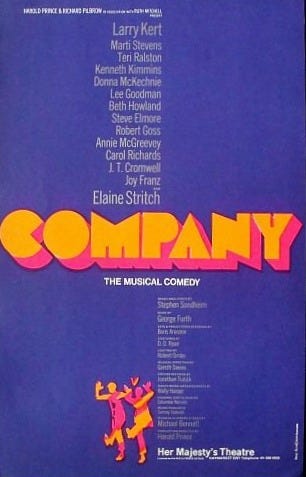

But the London trip in January 1972 proved to be equally life-changing. First of all, because, well, London. Even in the freezing rain of a London winter, shivering backstage at the Mountview Drama School, I could tell this city was a special place. My castmates and I attended a production of Long Day’s Journey into Night with Laurence Olivier on the West End—not too shabby, right? And then we decided to buy tickets to a musical called Company, in a production at Her Majesty’s Theatre featuring most of the actors who had appeared in its Broadway premiere a year or so earlier.

I don’t know why I bought the ticket, or what I expected. I mean, Olivier, Long Day’s Journey—we all knew that would be epic, and it didn’t disappoint. But Company?

It was my first encounter with the work of Stephen Sondheim and Hal Prince, and like Mass, it was life-changing.

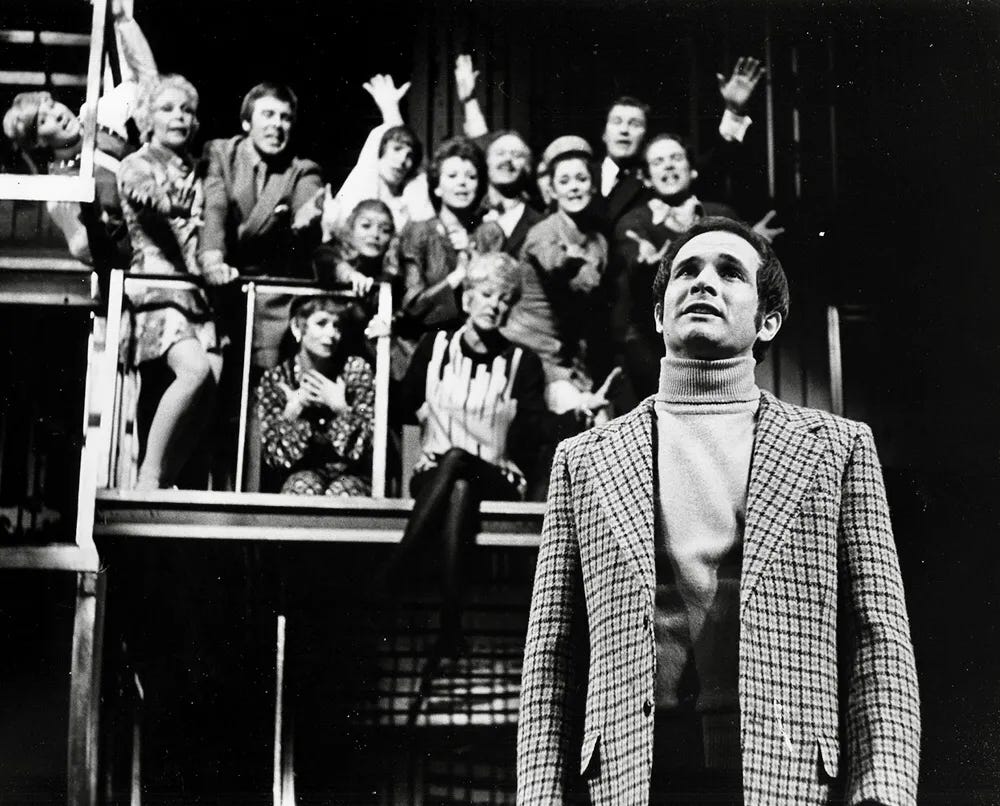

But where Mass had been epic, sprawling, and overwhelming—a work that confronted you with its sheer scale and spiritual ambition—Company was sleek, urbane, and devastatingly precise. If Mass was a detonation, Company was a surgical incision.

My experiences with musicals in high school had done nothing to prepare me for a first-class West End musical, let alone one as stylish and innovative as this. I was a suburban kid, and city life was foreign to me. I knew nothing of Manhattan, and my few days in London had been intense and intimidating—the crowded streets, the unfamiliar accents, the sheer density of it all. But what I saw and heard that night opened up so many possibilities.

The set itself was a revelation: Boris Aronson’s chrome-and-glass design, a gleaming modernist structure of elevators and platforms that seemed to embody the sleek, cold geometry of urban apartment living. It was beautiful and alienating at once. The opening number, “Company,” exploded with energy—friends calling out to Bobby, the central character, inviting him in, pulling at him, all while he remained somehow separate, observing. The music was rhythmically complex, jagged, insistent. The lyrics ricocheted with internal rhymes and overlapping voices. I had never heard anything like it.

And then came the songs, one after another, each one a small, perfectly crafted world. “The Little Things You Do Together” was witty and acidic, a catalog of marital compromises sung with a smile that barely concealed its cynicism. “Getting Married Today” was a virtuosic patter song—Amy’s terrified monologue racing against the clock, breathless and hilarious and heartbreaking all at once. “Someone Is Waiting” was tender and searching. “The Ladies Who Lunch” was bitter and ferocious, Elaine Stritch stopping the show cold with a performance that was equal parts defiance and despair.

I didn’t understand all of it. The characters were navigating relationships, marriages, and emotional compromises that were far beyond my sixteen-year-old experience. But I felt it. I felt the loneliness beneath the wit, the yearning beneath the sophistication. And I understood, even if only intuitively, that this was a musical about what it meant to be alive in a modern city—about connection and isolation, about the challenges of commitment and the fear of being alone.

What struck me most was how intelligent it all was. Sondheim’s lyrics demanded attention—every line was loaded with meaning, every rhyme felt inevitable and surprising at the same time. The music didn’t just support the story; it was the story, revealing character and psychology in ways that dialogue alone never could. And the structure—episodic, non-linear, without a conventional plot—felt radical. There was no villain, no clear resolution, no triumphant finale where everything was neatly tied up. Bobby’s journey wasn’t about solving a problem; it was about realizing one. The final song, “Being Alive,” was a plea, a breakthrough, a moment of raw vulnerability that left me breathless.

I left the theater that night walking through the cold London streets in a daze. I had just seen a musical that treated its audience like adults, that assumed intelligence and emotional maturity, that didn’t need to spell everything out or wrap everything up. It was sexy, sophisticated, and heartbreaking. It was about loneliness and connection, about the compromises we make and the prices we pay. It was everything I didn’t know a musical could be.

If Mass had shown me that musical theater could be vast and unruly and dangerous, Company showed me it could be intimate, subtle, and psychologically complex. Together, these two works—encountered within four months of each other—redrew the map of what I thought was possible. They weren’t just musicals. They were art. And suddenly, the idea that I might spend my life making work like this didn’t seem absurd. It seemed essential.

Looking back from my current vantage point, it seems almost too perfect that I encountered these two works as a naive freshman in college. Two works that represent what came to be the heart of the work I decided to pursue as a student and later as a professional artist and educator. It’s like those experiences reverberated through the rest of my undergraduate experience.

Of course I bought the original cast album of Company, and played it incessantly, adding the two-disc recording of Mass to my heavy rotation as soon as it was released in 1972. Of course I created a movement piece for a class assignment using a section of Mass as the soundtrack. Of course I auditioned for Company when I heard that UD would be producing it, landing the role of David, and I added Anyone Can Whistle, Follies, and A Little Night Music to my record collection. And I directed a student production of Bernstein’s Trouble in Tahiti in my senior year, the capstone project in an interdisciplinary major in music and theater I designed for myself under the auspices of UD’s Dean’s Scholar program.

These two works—one epic and explosive, the other intimate and incisive—became the twin poles of my aesthetic education. Mass taught me that musical theater could be a site of spiritual and social interrogation, that it could refuse easy answers and embrace chaos, dissonance, and spectacle in service of a larger argument. Company taught me that musical theater could be psychologically sophisticated, that it could explore interiority and ambivalence, that wit and emotional depth were not opposites but could coexist in the same breath.

Together, they showed me that the form was capacious enough to contain multitudes—that it could be anything I wanted it to be, if I was willing to take the risks. They didn’t just change what I thought musical theater could do. They changed what I thought I could do.

I’m embarassed to note that, at the time, I didn’t know then that Sondheim and Bernstein had worked together to create West Side Story. I didn’t know that Sondheim had famously suggested that all the lyrics in Mass should be in Latin - a snide swipe at Bernstein and Stephen Schwartz’s English texts. I didn’t know about Sondheim’s witty birthday tribute, “Poor Lenny, ten gifts too many,” which acknowledged Bernstein’s polymathic brilliance while also recognizing the burden of being “too good at doing too many things.” I didn’t know that the two men I revered had such a complicated relationship, marked by collaboration, competition, affection, and critique.

I didn’t know any of this because I was sixteen, and my enthusiasm was absolute and uncomplicated. I loved Mass for its audacity and Company for its intelligence, and it never occurred to me that one artist might view the other’s work with skepticism, or that the field I was entering was full of such tensions—aesthetic disagreements, personal rivalries, the challenges of sustaining a career in an art form that demanded so much and offered so little certainty.

I had tremendous youthful enthusiasm. But I still had a lot to learn about the challenges and possibilities of a career in musical theater. What I did have, though, was a compass. Mass and Company had shown me two paths forward, two ways of thinking about what the form could be. And even if I didn’t yet understand the complexities, the compromises, or the struggles that lay ahead, I knew where I wanted to go.

I am trying to write about Company right now for my similarly theater themed blog and you are really putting things into words that I am struggling to. “far beyond my sixteen-year-old experience. But I felt it.” Yes. “What struck me most was how intelligent it all was.” Yes.

I love this show and what a wonder that it is that this came along my feed now.

Thank you.